Sebastião Salgado - An Analogue Soul in a Digital World

A Personal Tribute to the Master Who Bridged Two Eras of Photography

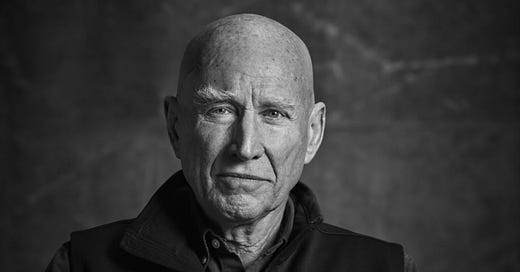

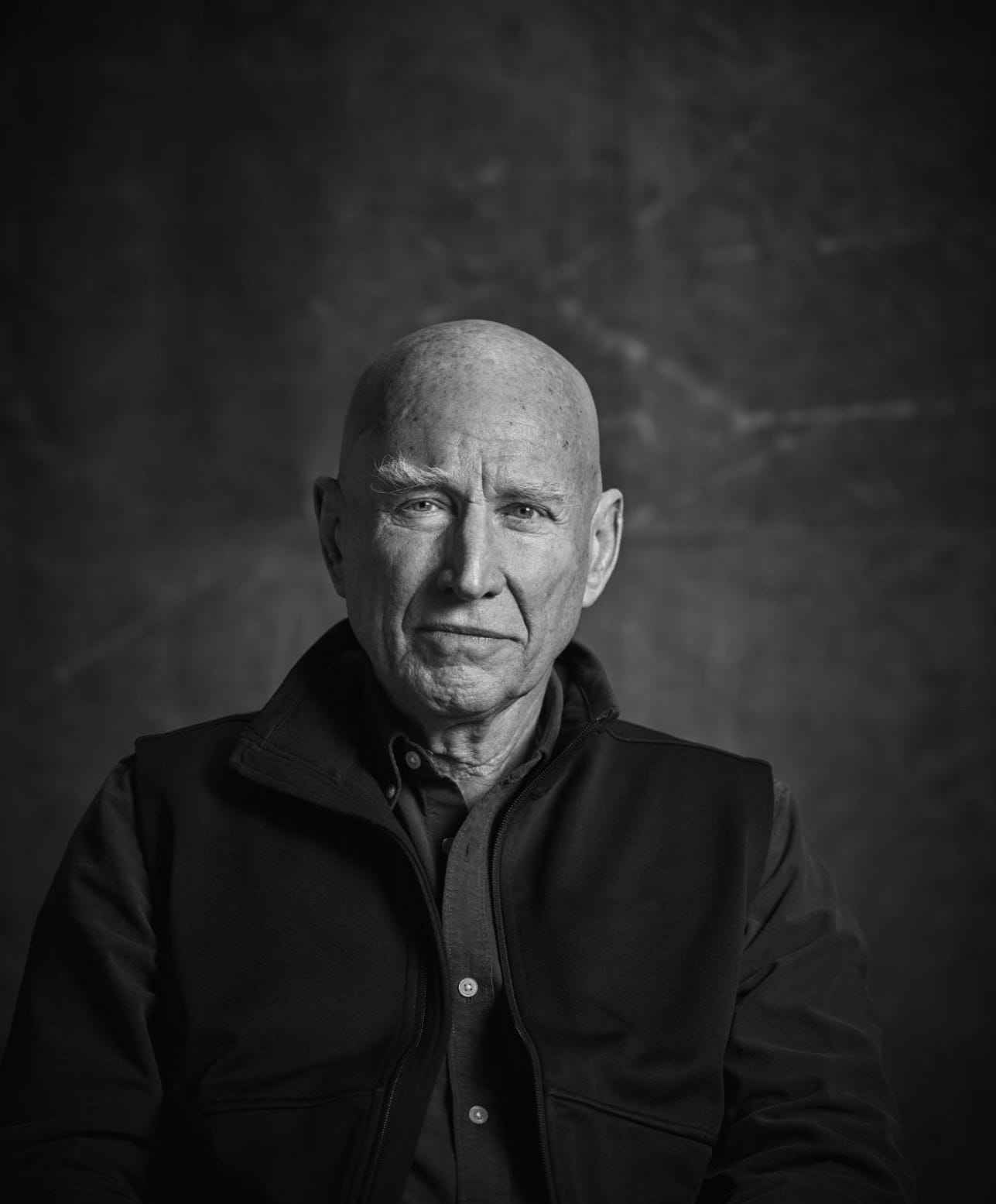

In memoriam: Sebastião Salgado (1944-2025)

Yesterday, the photography world lost one of its greatest luminaries. Sebastião Salgado died at 81 from Leukaemia, his family confirmed on Friday, 23rd May, marking the end of an extraordinary journey that spanned over five decades and revolutionised how we see humanity, nature, and our responsibility to both.

For me, this loss is profoundly personal. Sebastião was not merely a photographer I admired from afar, he was a mentor, a guide, and the beacon who led me back to my true calling when I had lost my way.

I had the extraordinary privilege of a personal one-to-one discussion with Sebastião in London, prior to the opening of Genesis at the Natural History Museum where he delivered the keynote speech before the exhibition's launch in 2013. This wasn't just a meeting, it became a mentorship that would fundamentally change the trajectory of my life.

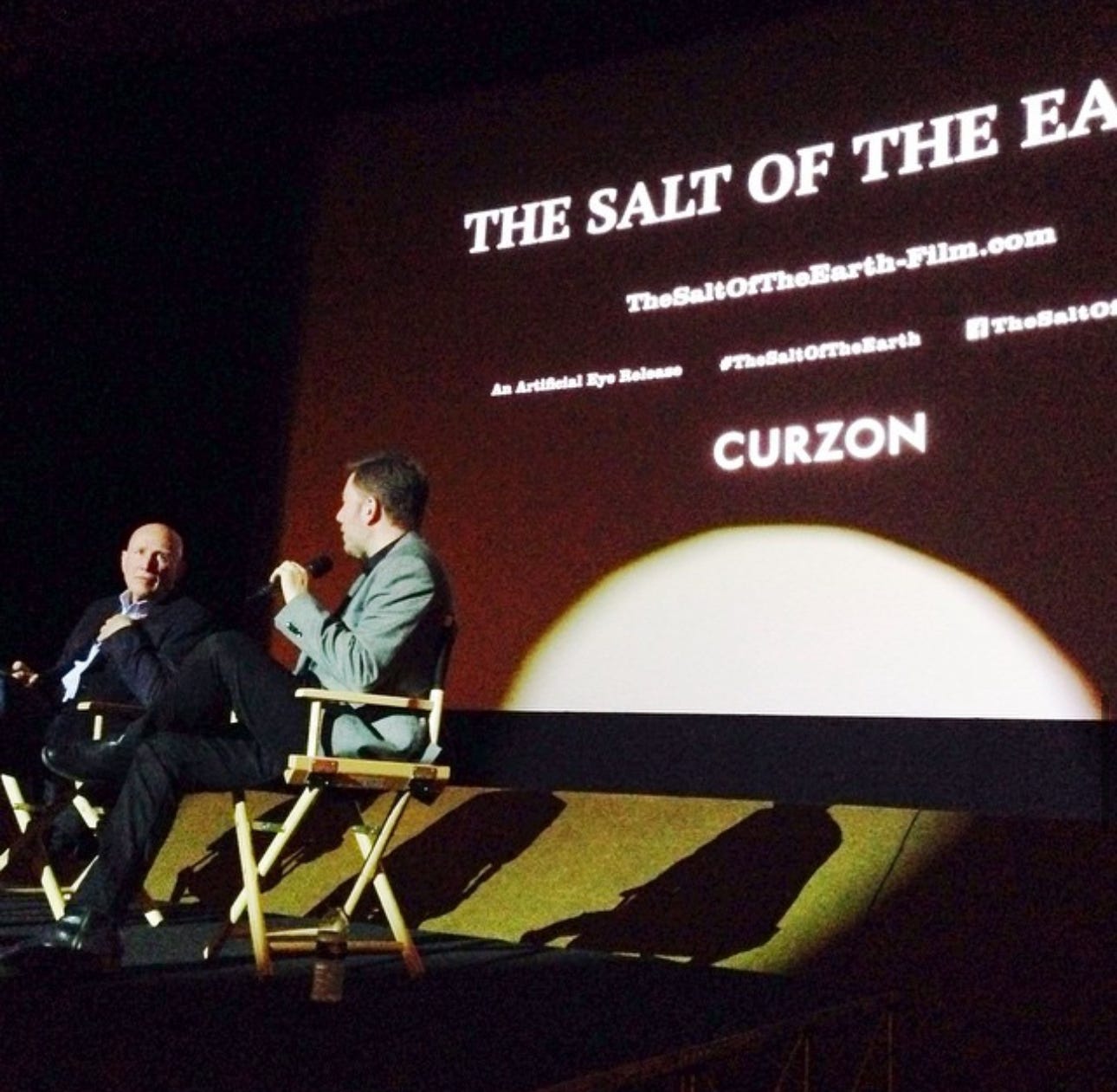

Our relationship, though built on only a few precious encounters, was one I treasured deeply. The depth of his recognition of me became clear at the Q&A Premier Screening of 'The Salt of The Earth' at the Curzon in Chelsea, London in 2014. The evening had been wonderful to see the movie premier, but became somewhat disappointing when the Q&A began, hosted by a Guardian newspaper reporter (I forget his name) the questions I thought were frankly crass, asking about his "favourite photograph" and other superficial queries that seemed to miss entirely the profundity of Sebastião's work and vision.

When the opportunity arose for audience questions, I had the last, I knew I had to ask what we were all truly thinking, but not yet broached. At 70 years old in 2014, having just completed the monumental eight-year Genesis project, surely the question burning in everyone's mind was about his future. I stood and asked: "Sebastião, I am sure that we all want to know if you shall continue working on a new project and indeed that the word ‘retirement’ is not in your personal lexicon."

The moment I spoke, I saw recognition in his eyes. He knew who I was, I had been in the front row and had patiently waited to speak. What followed was a direct, face-to-face ten-minute response that was nothing short of mesmerising. He spoke with passion about his plans going forward, his continued commitment to bearing witness to our world, and his vision for what would eventually become the Amazônia project. In that exchange, before a packed cinema audience, Sebastião gave us a glimpse into the restless creative spirit that drove him, the understanding that for someone like him, there could be no retirement from the calling to document our world's beauty and fragility.

That evening reinforced what I had learned in our private conversation. Sebastião understood that true photographers are not people who simply take pictures, but individuals compelled to engage with the world through their cameras. His recognition of me, his willingness to engage so deeply with my question, spoke to the generosity of spirit that made him not just a great photographer, but a great human being.

What struck me most profoundly during our conversations was not just his legendary humility or the intensity of his gaze, but his warmth and how he had managed to remain fundamentally an analogue photographer in an increasingly digital world. His approach to this technological transition offers profound lessons for our entire generation of photographers, but more than that, it showed me how to maintain artistic integrity regardless of the tools at hand.

Sebastião's influence on my life extends far beyond technical knowledge. When we met before the Genesis opening, I was at a crossroads, having left photography for financial security in the world of property, yet feeling an emptiness that success couldn't fill. In our conversation, Sebastião didn't simply discuss cameras or technique. He spoke about photography as a language of humanity, a means of connection that transcends commercial considerations.

"Photography is much more than just taking pictures," he told the audience that evening, "it is a way of life. What you feel, what you want to express, is your ideology and your ethics." But in our private discussion, he made it personal; he understood the pull of practical concerns, but reminded me that some callings are too important to abandon entirely.

His encouragement wasn't just words, it was the example of his own life. Here was someone who had left economics for photography, who had built not just a career but a mission from his camera. His gentle guidance and the inspiration of his unwavering commitment gave me the courage to return to the medium that had shaped my youth. In many ways, this tribute exists because of that conversation, because he reminded me that photography isn't just about making images, but about making meaning.

Salgado's technical journey mirrors the broader evolution of photography itself. He primarily used 35mm film cameras, such as the Leica M6 and the Canon EOS-1V, as well as medium format cameras like the Pentax 67 and the Mamiya 7, predominantly using Kodak Tri-X 400 black and white film. His early work, from the haunting images of Serra Pelada gold miners to his documentation of global migration, was born from this classical foundation.

However, as his projects became more ambitious, particularly during Genesis, his practical necessities forced adaptation, taking hundreds of rolls of film through countless airport security checks and the overzealous intensity of X-ray screenings on the film takes its toll and important images never to be reshot again were degraded. Thus, a switch to digital was decided - Since 2008 he has been using Canon's EOS-1Ds Mark III and more recently the EOS-1D X initially with the review screen blacked out as if he was still shooting film (no immediate review with film cameras). But this wasn't a simple switch to digital convenience. Instead, Salgado engineered something remarkable. A way to preserve his analogue soul in a digital body - metaphorically and also in reality.

What Sebastião developed was perhaps the most sophisticated film-digital hybrid workflow ever created. His digital captures > converted to film negative > to darkroom print workflow involved: shooting with a digital camera, RAW demosaic with exposure correction, processing with DxO Film Pack for Kodak Tri-X 400 or TMax 3200 film simulation, printing that image to a 4x5 technical film internegative, and finally printing the internegative to silver halide paper in the darkroom.

This wasn't mere nostalgia, it was artistic integrity. This workflow let him shoot digital images that look identical to his film images and result in a silver halide archival print and an archival negative that can be printed from in the future.

What fascinated me most about our London encounters was learning about his mental approach to digital capture. "I don't look at the back of the camera after I take a picture. I only look [at the end of a day's shoot] very quickly to see if there is a problem". He deliberately blacked out the review screen on his digital cameras to emulate the uncertainty and anticipation of film, that beautiful tension of not knowing what you had until development.

Even more remarkably, he never used a computer. He had contact sheets produced and edited with a loupe. After each expedition, he returned to his Paris office with around 10,000+ pictures. He edits all of the images himself, but not on screen. In fact, he never used a computer (his team did the digital to analogue work). This commitment to tactile, physical interaction with his images, the feel of paper, the magnification of a loupe, the ritual of marking contact sheets with a chinagraph pencil kept him connected to photography's essential humanity. In our discussions, this approach seemed central to his philosophy: that the image must exist as a physical reality to be truly understood.

Sebastião worked closely with the best of professional printers such as master printer Pablo Inirio, the renowned Magnum Photos darkroom printer in New York, whom now works from the Bronx Documentary Centre, to produce his photographs as ‘silver gelatin prints’, using traditional darkroom techniques to achieve exceptional tonal range and detail. This collaboration represents something profound: in an age of instant digital output, Sebastião maintained that the image wasn't complete until it existed as a physical object, crafted by human hands in chemical baths under the glow of a safelight.

His prints weren't just photographs, they were artefacts of a process, bearing the mark of human intervention at every stage. The grain structure, the tonal gradations, the subtle variations that only emerge through traditional printing, these weren't stylistic choices but fundamental expressions of his artistic philosophy.

For photographers like myself, who witnessed this transition from film to digital and who have experienced our own career detours and returns, Sebastião's approach offers a roadmap for preserving photographic integrity in any circumstances. He showed us that technology should serve vision, not dictate it, even more so in an age of AI. It seems that the tools may change, that life may take us down different paths, but the essential act of seeing and of bearing witness to the world's beauty and suffering remains unchanged and fundamental to the integrity of photography.

During our London conversations, he spoke about the importance of commitment to one's vision, regardless of external pressures or practical considerations. This wisdom guided me through my own return to photography, teaching me that authenticity in the medium comes not from the equipment we use, but from the sincerity of our engagement with the world. His influence extends beyond technique to philosophy. Sebastião's straightforward photographs portray individuals living in desperate economic circumstances. Because he insists on presenting his pictures in series, rather than individually, and because each work's point of view refuses to separate subject from context, Sebastião achieves a difficult task. He taught us that photography is not about individual moments but about sustained engagement with the world - That I see as a mantra and a way of life.

“Sebastião was much more than one of the greatest photographers of our time," said his nonprofit Instituto Terra. Alongside his life partner, Lélia Wanick Salgado, he sowed hope where there was devastation and brought to life the belief that environmental restoration is also a profound act of love for humanity.

His final major work, Amazônia, completed just years before his death, stands as both artistic masterpiece and urgent environmental warning. "My wish, with all my heart, with all my energy, with all the passion I possess, is that in 50 years' time this book will not resemble a record of a lost world. Amazônia must live on".

Sebastião's death marks the end of an era, but his legacy lives in multiple dimensions. Through Instituto Terra, he succeeded in turning 17,000 acres into a nature reserve, dedicated to a mission of reforestation, conservation and environmental education. Through his images, he documented the 20th and early 21st centuries with unmatched empathy and artistic vision. Through his technical innovations, he showed how to honour tradition while embracing necessary change.

For those of us who followed in his footsteps, who struggled with our own transitions from film to digital, who questioned whether we were losing something essential in the process, Sebastião provided the answer. We lose nothing if we refuse to surrender our humanity to our tools. For those of us blessed to know him personally, he provided something even more precious; the understanding that photography is ultimately about connection, compassion, and the courage to continue bearing witness to our world.

"Photography is the language that gives people the opportunity to see what you saw", he once said. In our increasingly mediated world, this simple truth becomes revolutionary. Salgado saw clearly, felt deeply, and shared both with the world through images that will endure long after their pixels have been forgotten.

He was, as he showed us how to be, an analogue soul in a digital world, never forgetting that behind every image is a human being with a story worth telling, and that our job as photographers is to tell those stories with all the technical skill and human compassion we can muster. In losing Sebastião, We have lost not just a photographic giant, but a mentor, whose wisdom guided me back to my truest calling. His legacy lives on not only in his extraordinary body of work, but in every photographer who chooses humanity over convenience, depth over speed, and meaning over mere imagery.

About the Author

Murray (Buzz) Russell-Langton is a Bangkok-based photographer, originally based in London, renowned for his award-winning interior and architectural photography. His client base includes digital agencies, architects, interior designers, hotels, resorts and private commissions creating content for editorial, advertising, and social media applications. He operates One Create Agency, as creative director, a multimedia production company and publisher of One Create Magazine where he is the editor-in-chief.

Buzz’s photographic foundation was built in traditional black and white darkrooms, where he developed skills in fine art printing and analogue techniques. This early training established his approach to lighting and workflow methods that would later align with the philosophies he encountered through his mentorship with Sebastião Salgado.

His personal work continues to explore black and white photography, maintaining connections to traditional photographic processes alongside his commercial practice. Russell-Langton's technical approach emphasises capturing images in-camera through careful lighting rather than extensive post-production, utilising continuous LED lighting, speed-lights, and studio flash as needed for interior photography.

The principles learned through his early darkroom experience and later reinforced through his encounters with Salgado continue to inform his work, whether documenting architectural spaces or pursuing personal projects that explore the human elements of photography.

Buzz as he is known to his friends and colleagues can be found via his personal website https://buzz-photography.com showcasing his architectural and interior work.